Some people bite the hand that feeds them. American Fiction’s Thelonious “Monk” Ellison wants to chew it whole and spit it back out.

Before we get there, first this: American Fiction is funny. It’s easily among the funniest movies I saw last year. If you see it with an audience half as engaged as the one at the Denver Film Festival, where it was the opening night attraction, you’ll need a second viewing just to get all the jokes in writer-director Cord Jefferson’s script.

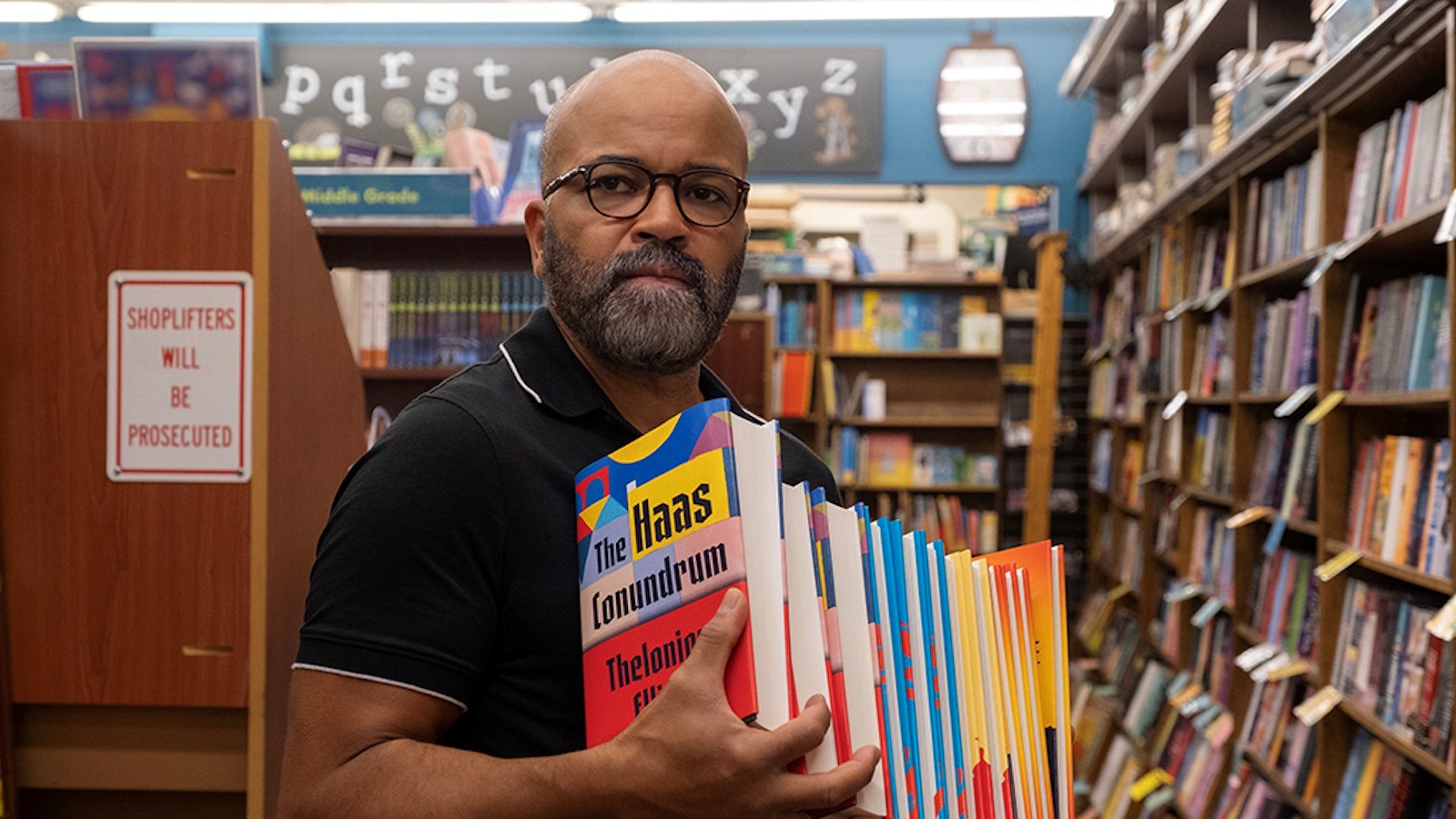

But American Fiction is also quite caustic. Based on the 2001 novel Erasure by Percival Everett, the film centers on Monk (Jeffrey Wright), a writer with high standards and low sales who has just written a very childish book trafficking in over-the-top Black stereotypes. It’s bad in an obvious way, and Monk knows that; it’s what he was aiming for. What he didn’t expect — though maybe should have — was that the worse the quality of the book, the more people would want to buy it, read it and praise it as a work of authentic expression. Now, a publisher is ready to ink a deal for three-quarters of a million dollars, with movie rights netting a cool seven figures.

Monk wants to walk away and reveal that the book — which he has retitled with an obscenity in hopes of killing the deal — was a pointed criticism of the publishing industry and nothing more. But Monk’s agent, Arthur (John Ortiz), refuses his ideology. Who cares about principles when there’s money to be made? Monk, that’s who. So Arthur provides him with American Fiction’s central metaphor: Johnnie Walker scotch.

For the non-drinking crowd, Johnnie Walker is a popular brand of blended scotch whisky you can find just about anywhere. The most common is Red Label, which isn’t great but sells for $25 a bottle. The Black Label is a bit better and costs $50. Then there is the lauded Blue Label, which retails for a couple hundred dollars a bottle. Try all three side-by-side, and there’s little doubt that Blue Label is measurably better than Red. But Red sells more bottles of scotch than Blue could ever dream of.

Do you see where Arthur is going with this? Of course you do — there are parallel examples in practically every industry. But where Arthur’s metaphor falters is in his belief that Monk could be Johnnie Walker and use his poorly written exploitation of Black trauma to fund his highbrow novels. In reality, the publishing industry is Johnnie Walker, and Arthur, knowingly or not, is trying to convince Monk to accept his role as a Red Label writer.

How much American Fiction wants the audience in on that distinction is up for debate. Monk is a cliché, grumpy, selfish artist with daddy issues pushing everyone away. His brother, Cliff (Sterling K. Brown) — a recently out-of-the-closet plastic surgeon with a drinking problem, a nose full of coke and a revolving door of boy toys — is also cliché. And they’re both funny as hell. So funny it’s hard to tell if Jefferson is mocking them or inviting the audience to laugh along with him.

The only one not a caricature is Coraline (Erika Alexander), Monk’s neighbor and love interest. She’s recently separated from her partner and ready for the next step. She finds that in Monk, a person she thinks is funny. Not ha-ha funny, but sad funny — like a three-legged dog. Cliff laughs the hardest when he hears that one.

Coraline has read one of Monk’s books and liked it. She has opinions and tastes. And Monk throws all of that out the window when he discovers she’s reading his fake book and likes that one, too. Coraline is the audience that can appreciate Red Label and Blue Label without contradiction. Monk has no time for that.

And yet, Monk is the hero of American Fiction, through which Jefferson seems to speak the clearest. And not because Monk is full of wisdom, but because he is filled with frustration about what he wants to say versus what he has to say to get attention. No wonder the movie’s “choose your own adventure” ending is presented more with a shrug than a shout. Sometimes the hand bites back.

ON SCREEN: American Fiction opens in wide release Jan. 5.