Whether it’s skiing champagne powder in the mountains or floating down one of the state’s rivers, Coloradans interact with water in more ways than one.

But out of view, there’s another part of the picture.

Nineteen of the state’s 64 counties “rely heavily” on groundwater, according to Water Education Colorado. Some of those areas, like the San Luis Valley, south Denver and the eastern plains, are having to reevaluate water usage as more wells deplete the available resource. That’s also happening nationally, as an investigation from the New York Times found that aquifers around the country are being “severely depleted” due to farming, residential development and less precipitation.

Water use in this state mostly comes from the surface (rivers and streams), but reliance on groundwater is increasing. Meanwhile, a recent study published in the Journal of Climate predicted Colorado River flows could increase between 2026 and 2050, but demonstrate heightened variability in the shape of “extreme low and high flows.”

Boulder County is somewhat sheltered from these realities — most residents are served by municipal utilities that almost exclusively draw from the surface water, with rights that give them first dibs.

But not all of those people are connected to city water. There are just over 10,000 wells hooked up to groundwater, most of them permitted for certain uses with minimal regulatory oversight standards or monitoring requirements.

While these “exempt” wells aren’t allowed to use as much water as larger capacity wells used for irrigation or commercial business, Boulder County Public Health (BCPH) water quality and sustainability specialist Erin Dodge said they are in a “regulatory gap,” making people more vulnerable to issues in water quality and quantity.

“Private well owners are basically completely unregulated,” Dodge said.

When monitoring does happen in the county, it’s collected by a patchwork of entities, making it difficult to discern long-term trends and creating uncertainty related to how growing human consumption and environmental factors, like climate change or drought, are impacting the system.

“We want to understand groundwater as well as we understand surface water. Surface water is a lot more sexy and it’s easier to measure, and people are excited about it because they can walk along the river,” said Tim Wellman, who sits on Shannon Water and Sanitation District’s (SWSD) board of directors in unincorporated Boulder County. “But measuring groundwater more effectively would help us understand the long term and be able to make some better decisions.”

What is groundwater?

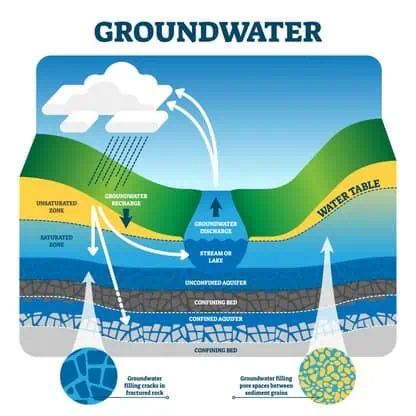

More than 95% of all freshwater in the world, excluding the polar ice caps, is groundwater. It’s found almost everywhere, depending on geology, as water fills empty spaces beneath the surface. The source of all groundwater is precipitation: rain, snow, sleet, hail and all other liquid that falls from the sky.

It’s hard to say exactly how many people rely on the water that collects naturally below the surface in the Centennial State. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) says it supplies around 11% of the state’s population, while the Colorado Geological Survey puts it closer to 20%.

A comprehensive assessment of the resource underfoot in Colorado has never been completed, but it’s estimated to be significant. Water Education Colorado’s Citizen Guide calls it “a vital and perhaps under-appreciated piece of the state’s water portfolio.”

There are more than 285,000 permits currently issued for wells in Colorado and 4,000 new ones requested per year to the state’s overseeing agency, the Division of Water Resources (DWR). Nearly 80% of the wells in Colorado are for domestic or household use, but irrigation draws 86% of the total groundwater used in the state.

There are three different kinds of rock or sediment that hold groundwater, called aquifers, found in Boulder County, each with their own distinct properties.

In the mountains are igneous aquifers that trap water in rock fractures and faults, such as granite, that have limited connectivity and often different water levels and yields. Shallow alluvial aquifers on the plains are made up of materials saturated with water and considered “tributary,” meaning they are connected to the surface water system. Finally, the southeast part of the county beneath sections of Broomfield and Louisville is above the Laramie-Fox Hills aquifer, the deepest of four bedrock aquifers in a geological formation from Greeley to Colorado Springs called the Denver Basin.

According to state data, the vast majority of wells constructed in the county don’t have a specified source aquifer, but multiple sources said most groundwater users tap into alluvial and granite systems.

What’s coming in and going out

When it comes to groundwater levels, Lesley Sebol, a senior hydrogeologist at the Colorado Geological Survey, said it’s a limited dataset and surveillance tends to focus more on quality.

“Water level data is the least monitored groundwater dataset in the state,” Sebol wrote in an email responding to questions. “There is no one go-to resource.”

Historically, the USGS monitored 537 wells in Boulder County, dating back to 1949. But less than 100 of them took more than one water level measurement, and the last readings from those wells was in 1986.

Connor Newman, a groundwater specialist at the Colorado Water Science Center within the USGS, said the federal agency monitors based on the needs of the public, which have changed over time.

“In essence, this means that in the early 1970s through mid-1980s, it appears to me that local agencies (Boulder County) had a keen interest in understanding groundwater resources,” Newman wrote in an email to Boulder Weekly, “but that those interests decreased through time.”

Today, BCPH water quality specialist Carl Job says “when it comes to ongoing groundwater monitoring, both in terms of quality and quantity, there’s not a whole lot of that going on [in Boulder County].”

DWR is the primary regulatory authority of water in the state. It administers water rights, monitors streamflow and water use, maintains databases of water information and gives out permits. Because groundwater and surface water are often connected, Colorado regulates groundwater within its system of “prior appropriation” unless proven otherwise.

The agency has a network of well monitoring across the Denver Basin. One of them, the only in Boulder County, has recorded water levels dropping nearly 30 feet between 2005 and 2023 at that point in the Laramie-Fox Hills aquifer. One year recorded 150 feet of fluctuation.

When asked about the potential causes of those changes, a county spokesperson said “groundwater levels are influenced by a variety of different factors. Large fluctuations over short intervals of time are often a result of groundwater pumping.”

According to state records, SWSD is the largest public water supplier that solely uses groundwater to serve a community (450 people) in Boulder County. Wellman said SWSD’s three wells are allocated up to 29.6 million gallons of pumping a year from the Laramie-Fox Hills aquifer, but they actually use about 10% of that.

The district doesn’t have ongoing water level testing, but Wellman found its wells “recharged quickly” after a recent test. As a public water provider, SWSD faces stricter regulations than exempt wells, but Wellman said water level surveillance “is really gallons pumped.”

“I think we want to understand the resource better, which means more monitoring wells to measure what the aquifer is doing,” Wellman said. “That would help us understand the overall amount of groundwater available and whether or not we are depleting it at a really fast rate … or if it’s more of a sustainable use.”

Since 2000, there has been an average of about 100 wells built in Boulder County per year. Most of them are private, exempt wells designated for domestic or household use and limited to pumping 15 gallons per minute, much less than other well uses such as irrigation.

Sustainability of the aquifer is not considered when evaluating exempt well permits because it isn’t required in statute, according to DWR officials. Job said there’s “ambiguity” around total water consumption with private wells because they are not regulated the same way as public systems like SWSD.

“Once the wells are in the ground, they’re kind of operating under their own oversight,” said Job about the roughly 9,650 exempt wells in the county.

The cities and towns of Lyons, Boulder, Lafayette and Superior all told Boulder Weekly they do not use groundwater and have no plans to develop it for public use in the future. Reasons varied from having adequate surface water supplies to a lack of nearby quality aquifers.

The City of Louisville has done some “basic high-level evaluations” of using groundwater, but it doesn’t have plans to advance the resource’s development, according to the city.

A spokesperson for one town, Erie, said the town anticipates up to 20% of its future maximum daily demand to come from groundwater, which will be augmented using water from Windy Gap reservoir. Augmentation plans are a way to replace water after pumping and are often required for “non-exempt” wells, like those permitted for subdivisions and municipalities providing public drinking water.

The City of Longmont also relies almost completely on surface water, said water resources manager Ken Huson, but it does have conditional rights for around 20 non-exempt well sites the city could drill. Huson said developing those wells is a long-term project and “further down the list of priorities” to meet demand in dry periods.

“It allows us to retime the water where you can take the water when you’re in a drought and replace it during periods when you have an excess supply.”

Low priority

Part of the reason for limited water level monitoring in Boulder County is because it isn’t required, according to Corey DeAngelis, water resources engineer at DWR.

“We’re not going to start requiring everybody with a well to start reporting, or we’re not going to go out and monitor the groundwater necessarily, because we don’t have statutory authority,” he said. “We are really cautious to look at the law, that’s what drives us in our duties.”

Water managers agree that more monitoring is better, but said it isn’t a priority because surface water is more readily available and used in the area.

“We’re so high up in the watershed [in Boulder County] that it may be over the top to try to monitor groundwater up here,” said Wellman, adding that equipment used to measure water levels, like pressure transducers, can cost up to $800 per well.

When asked about the depth of knowledge regarding groundwater levels and resources in Boulder County, Kevin Donegan, chief of DWR’s hydroecology section, said “it is going to be pretty restricted to private landowner, individual well records” because his office focuses more on monitoring areas where groundwater is the only supply, like other parts of the Denver Basin.

Boulder County’s varying types of groundwater also means that not all aquifers are interconnected, and even individual aquifer characteristics like depth and quality can change significantly. Much of the space around Boulder and Longmont is also known as the “Boulder Complex Area” where, due to the nearby mountains, a series of faults creates complicated geological layers, limiting groundwater supply.

Reid Polmanteer, a hydrologist who works with the Colorado Groundwater Association, said that increases the value of localized testing.

“The best monitoring point for a person reliant on groundwater is their own water well,” he wrote in response to emailed questions.

In areas without monitoring, DeAngelis said DWR generally might start “when there is an issue or something changes that could be problematic.”

“If it’s not an issue or a problem, then maybe that’s why there’s not the requirement, because it would take effort, reporting and more requirements on individual well owners to monitor and report all of that to us,” said DeAngelis. “And then the big question is well, why are we doing this?”

Deep dive

Over the last year and a half, BCPH has received funding from the sustainability tax, approved by Boulder County voters in 2016, to “think about how water quality and quantity are impacting our most vulnerable populations.”

Part of that effort has meant reaching out to private well owners to better understand groundwater and moving beyond what Dodge called “textbook knowledge” to a “data-driven, true understanding of the state of water quality and quantity in our county.”

In one project, the county discovered elevated levels of PFAS, otherwise known as forever chemicals, in private wells within the Sugarloaf and Boulder Mountain fire protection districts. Other areas found trace amounts of uranium.

In some cases, water levels may drop below a pump intake, also known as wells going “dry.” The state doesn’t track those occurrences, but BCPH said they’ve heard anecdotal reports of that and reduced pumping rates happening in the county.

Job said to understand groundwater level trends, especially relating to the influence of climate change and drought, long-term groundwater level records are needed — something that isn’t available.

“You need consistent groundwater level measurements being taken at dedicated monitor wells,” he said. “From the research we’ve done here in the last couple of months especially, there seems to be an absence of a lot of that taking place throughout the county.”

Boulder County as a government agency isn’t a water provider, unlike other municipalities in the area. Dodge said the county is still figuring out its role moving forward.

“We have upward of 10,000 wells in the county,” she said. “And I think it’s one of those questions that at some point, we’ll have to have a conversation and the county will ultimately need to decide what our role will be in supporting that community that’s not really part of a larger planning effort.”

Amid increasing demand and growing populations, Wellman said there should be more awareness regarding the ways we use water.

“The challenge is consciousness at the tap, at the household level, and all the way up through larger water users,” he said. “Elevating consciousness around overall water use and trying to get at that sustainability, and the reality that a lot of this water is finite.”