When you think about labor unions, industries like automotive or steelworks might spring to mind. However, such worker collectives span an array of professions. Among these, the Actors’ Equity Association (AEA), known as Equity by its members, is the only union for actors and stage managers in the performing arts.

“My retirement plan, healthcare and safety protections are the most important benefits I receive,” says Abner Genece, an Equity actor and the union’s co-community leader in Denver. “However, joining is a highly personal decision, as union membership is not a one-size-fits-all situation.”

That choice — to join, continue union membership or leave — has become harder in recent years, stage workers say, with cuts to benefits coming during a COVID-forced work slowdown and what some actors feel is too much focus on larger markets, to the detriment of smaller ones like Colorado.

Union representatives admit that “many members” lost coverage during the global health crisis. Among them was long-time local Equity member Piper Arpan McTaggart. An active member since the early 2000s, McTaggart spent years on Broadway before moving to Colorado in late 2009, where she was able to work on Equity contracts.

“The reason I dropped was 100% due to Equity’s response to COVID,” McTaggart says. “Equity said, ‘Pay your dues,’ but they would not let us work. I lost insurance for myself, my son and my husband. I didn’t feel supported by Equity, and non-Equity houses were making it work, so I couldn’t resist.”

Equity is taking steps to address members’ concerns. Local leaders are optimistic that the energy bolstering workers rights nationally will enliven their own industry, bringing a brighter future to stages across Colorado.

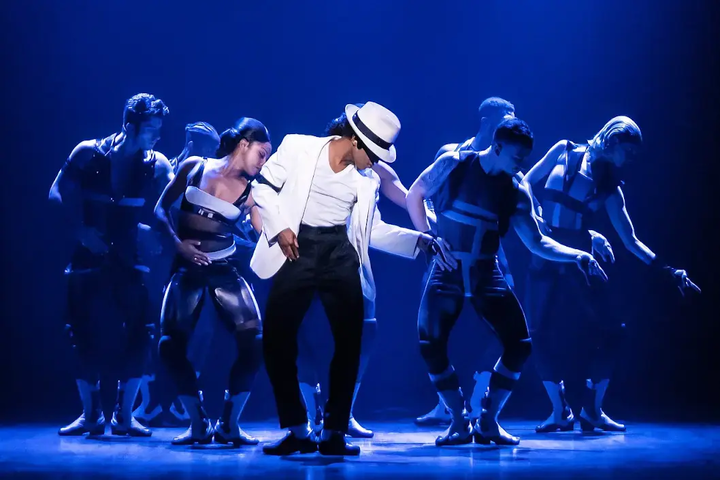

Courtesy: Actors’ Equity Association

The good, the bad and the ugly

Most people have seen an Equity actor on stage, often denoted by an asterisk in programs, or attended a union tour at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts (DCPA) like the recent MJ or upcoming Company. Union tours are subject to Equity’s rules surrounding working conditions and benefits, while non-union tours don’t have to provide the same protections.

Founded in 1913 and officially recognized by the American Federation of Labor six years later, Equity has long advocated for better working conditions for stage workers. From organizing the first strike in American theater history to fighting for civil rights, the union has been at the forefront of many arts labor movements since its inception more than a century ago.

Today, Equity has approximately 51,000 members, with Colorado accounting for just under 400, mostly in the Denver and Boulder areas. Union representatives say membership has “gradually increased” over the last several years, but some locals say it remains difficult to make a living as a union artist in the area.

“Coloradans face a lot of the issues that members do outside of the three biggest theater markets of Los Angeles, Chicago and New York: There is only so much theater work to go around,” says Gabriela Geselowitz, senior writer and project manager for Equity. “That said, Denver has a few large venues and companies that have helped sustain theater in the metro area.”

The theater scene in Colorado operates on a smaller scale than the sprawling productions seen on Broadway. Equity houses like the DCPA, Lone Tree Arts Center, Colorado Shakespeare Festival and Arvada Center frequently hire union performers through League of Resident Theatres (LORT) contracts, which typically include higher salary scales and benefits.

In contrast, Small Professional Theatre (SPT) agreements are more flexible, allowing venues like the Boulder Ensemble Theatre Company, Local Theater Company, Miners Alley Playhouse and others to offer some Equity contracts without the financial strain associated with LORT terms.

With additional payroll taxes and contributions to healthcare and pension plans, union actors are roughly twice as expensive to hire.

Contract benefits include negotiated minimum wages, rules ensuring safe working conditions, set working hours, health insurance and more. They also have access to Equity’s staff to enforce contracts, and increased access to auditions, educational programs and community events.

“We decided to become a union theater a few years ago because we believe in the union,” explains Len Matheo, Miners Alley’s artistic director. “If I could afford it, everyone would be on a union contract so that everyone could have health insurance. My goal is to hire more union workers, but I need to do so responsibly.”

More benefits, less work

Membership can come with drawbacks. Because of the small number of Equity engagements available in a market like Colorado’s, members are limited to fewer job opportunities than their non-union counterparts.

“I earn more money working out of state, even with all the travel expenses,” says Erin Joy Swank, Equity stage manager and Denver’s co-community leader. “It is a tricky situation because while I enjoy living in Denver, I cannot sustainably work here as a full-time Equity stage manager.”

Because of the lack of open union positions, members are often forced to choose between waiting for limited Equity positions and leaving the union to work for non-union companies.

“There are not enough Equity jobs in Colorado for me to live and work full-time,” says Jalyn Webb, a former Equity actor who cancelled her membership during the pandemic. “I love the non-Equity theaters we have here, so I dropped my union card because I wanted to work more than [I wanted to be] be a union member.”

COVID complications

The pandemic exacerbated existing challenges faced by union members. Previously, Equity’s healthcare requirements were based on a system in which members had to work a set number of weeks to qualify for insurance. Due to a lack of contributions to the health fund caused by canceled shows in the early days of COVID-19, Equity-League Benefit Funds — which manages union health insurance — increased qualification thresholds to levels that were hard for members to meet.

As the industry recovered, the requirements were reevaluated. Beginning in January, Equity-League implemented a simplified plan design, reinstating the pre-pandemic work requirements.

In 2021, Equity leadership loosened requirements for its membership criteria, which leadership said in a press release was intended to address systemic barriers and include more people. Some members accused the organization of using the change for financial gain, especially since many new members wouldn’t qualify for healthcare.

All the changes forced former McTaggart into what she calls the “heartbreaking” choice to leave the union.

“As an aspiring musical theater person, taking your card feels like such an accomplishment,” she says. “Dropping it felt counterintuitive, but the arts are my livelihood, so when I couldn’t perform, I was suffocating artistically and financially.”

Looking back, though, McTaggart feels it was the right move.

“I don’t have a single regret,” she says. “I am performing at more theaters, and financially, it’s a wash — I don’t get benefits anymore, but I also don’t have to pay working dues or fees.”

Others have come to grips with their gripes about Equity while maintaining their union membership.

“I can be a proud member while also having concerns about some of the policies they implemented,” says Betty Hart, Equity actor, Colorado Theatre Guild president and co-artistic director of Boulder’s Local Theater Company. “I believe the AEA should take into account what is happening in these smaller regions. We cannot get contracts specific to our area, which would allow us to work more while paying a rate closer to the Equity standard.”

The road ahead

Asked about the organization’s plans to improve services to those working in regional theater markets, Equity representatives said the union wanted to “[take] the lead from our members in the communities where they live about what is important to them.”

In late March of this year, Equity’s executive director, Al Vincent, Jr., embarked on a tour of Equity communities across the U.S., with a stop in Colorado, to gather insights from members.

Equity also relaunched its field representative program, which the organization says will enhance the union’s presence and engagement in various theatrical markets, including the Centennial State. According to Geselowitz, field representatives will have made a dozen in-person visits to Colorado theaters in just over a year.

As local volunteer leader Genece thinks about the future, he remains optimistic while acknowledging market realities.

“The union is very much a long-term plan, especially in regional markets,” Genece says. “I do not want to paint a bleak picture, because I believe things are gradually improving, but limited Equity contracts in Colorado are a reality, and each artist must decide what is best for them.”